Why? Because there’s no such thing as brakes that are ‘too good’ is there? Here’s everything you need to know about braking and upgraded performance brakes.

Better brakes make your car faster, it’s that simple. Think about it; a braking system that’s more effective means you have to spend less time using it. Less time on the anchors means more time on the throttle. All that adds up to being real-world quicker through the twisty stuff. And if you’re looking for best, check out our best brake pads and rotors in 2023.

Of course, that’s not the only reason why a cheeky performance brakes upgrade is one of the most popular chassis mods on a car out there. There’s also the real-world power tuning benefit. Most of the time, it’s far more cost effective to upgrade your braking system than the relative amount of engine work needed for the same outcome on the road or track.

What’s more, there’s nearly always room for improvement. Realistically, standard braking systems are built to a budget. They’re also specifically designed to handle a little over the standard power and relatively normal driving conditions. Throw a spot of extra tuning into the mix, or any sort of fruity right foot action, and upgrading your brakes becomes pretty essential.

Of course, performance brakes are also safer, and you can’t put a price on that, can you? So, here’s what you need to know about performance brakes.

Brake rotor and disc upgrades

The science

There are two things we’re looking for in an effective brake upgrade. The most obvious is improving vehicle stopping power by increasing the force that you can apply. The second is simply increasing the amount of heat the system can safely dissipate. In other words, reducing the chance of the hardware overheating.

Brake fade is the biggest problem when it comes to excess heat. However, you still need some for brakes to work. It’s the friction caused by the pad rubbing on the rotor (disc) that slows the car by converting the motion energy to heat energy. Obviously, the temperature increases with how hard and how much you use the brakes. It is this heat which needs to be dissipated effectively. Upgrades are designed to do both.

Drum brakes

It’s true that you don’t find drums on many modern cars. However, from a pure performance standpoint, drums are pretty effective up to point. The biggest problem they have is longevity. Under hard use, they generate and retain a huge amount of heat. This is why drums are notorious for being effective for a while then, rather suddenly, not at all. Drums can be also be grabby, going from nothing to total lockup in no time at all. In some cases they can even stay locked on when you let off the pedal.

There are some lightly uprated drums setups out there. The most common have grooves on the friction surface to help dissipate heat, or shoes with a softer performance compound. To be fair though, in the case of front brakes at least, you only find drums on the seriously old school classics. Even then many simply choose to upgrade to rotors.

Brake bias

What about drum brakes on the rear? Some manufacturers still fit drums on the rear of lower-end cars because they just aren’t needed as much as the big powerful rotors found on the front.

Science tells us that, when you hit the brakes, the momentum of the vehicle will cause most of the weight to shift forwards. This is why the vast majority of cars have larger brakes on the front than the rear. Of course, from a performance standpoint (and often when it comes to out-and-out looks) many choose to convert rear drums to rotors, whether you really need to or not. In that case, the key is always balance, with brakes on the rear that can overpower the front, you could be swapping ends in no time.

Most of the time the rear brakes are responsible for under 30-percent of the stopping power and used more for stability. In a rotor setup, you’ll nearly always find the rear brakes use smaller calipers and smaller, thinner (often solid) discs. Front discs however will usually be far beefier and most often vented in the middle to help with dissipation.

Disc / rotor brakes

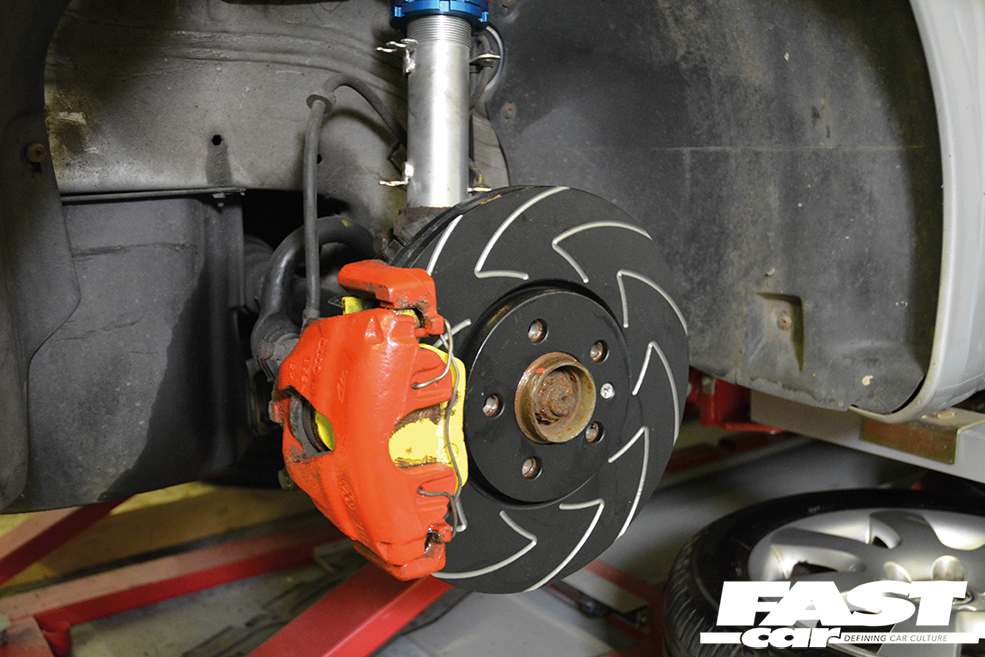

Unless you’re talking about cars of the retro variety, chances are you’ll find a set of rotors under your front arches. Luckily these have by far the widest range of upgrade options.

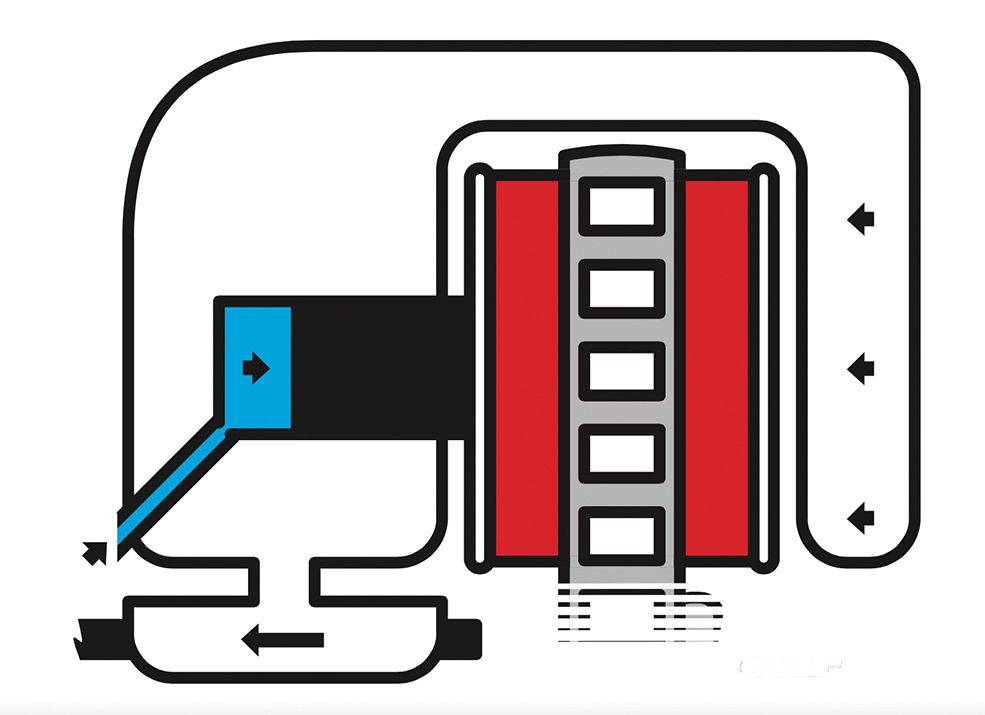

With a disc brake system there are three main parts to the hardware; the caliper assembly, disc or rotor and the pads. These all need to work in harmony to stop your car. The idea is actually pretty simple. It revolves around hydraulic fluid being forced at high pressure into the caliper.

Modern ‘power-assisted’ systems, use an in-line brake servo that amplifies the pressure you put on the master cylinder (via the pedal) using vacuum created by the engine. Old skool ‘non-servo’ systems rely more on pedal pressure. You’ll most commonly find these on classic cars, although many race cars have the same simple setup.

In both cases, when you put pressure on the middle pedal, the piston (or pistons) inside the caliper then extend out against the pads. In turn, these push against the rotor to produce the friction that slows down the car.

Upgrading the system revolves around increasing the bite of the pads (through the choice of compound), the clamping force that can be applied by the calipers and the leverage on the disc. Not forgetting, the ability of the whole lot to effectively dissipate the heat produced.

Brake Rotor / Disc sizes

The simple fact of the matter is that bigger rotors give better performance. A larger disc has more surface area for the pad to bite and to dissipate heat. You also get more leverage when the caliper clamps down on the outside edge. It’s the same with larger calipers, usually these will be able to produce much more clamping force than smaller items.

There are a couple of limitations when it comes to fitting larger discs. The first is the size of your alloy wheels. After all, they do need to fit inside them! It’s also worth remembering that, while many OEM upgrades and big brake kits offer lightweight alloy calipers, putting enormous rotors on a car that doesn’t need it will inevitably increase weight. As with anything, the key for optimum performance is finding the right balance.

Performance brakes – rotor / disc upgrades

Direct fit upgrades

The simplest of disc upgrades is a direct-fit (standard-sized) disc with a performance-orientated surface treatment. These provide an effective hike in braking performance for minimum outlay. They are also as simple to install as standard items. The important thing here, apart from ease of fitment, is the surface treatment, here’s the most common ones you’ll find.

Grooved rotors / discs

These have a number of grooves machined into the face designed to clean off the glaze that builds up on the pads under heavy breaking. This increases the ‘bite’ of the pads and, to some extent, also provides channels to vent gases produced between the disc and pad. There’s a whole load of different designs, but the principle is always the same.

Cross drilled rotors / discs

In this case, a number of drilled holes in the friction surface help expel the gases and dust through the disc and out of vents in the middle. They also offer a varied surface for the pads to bite to. Although these aren’t common on standard road cars, a few modern performance models and plenty of supercars will come with these from the factory. They’ve been common in motorsport since the ‘60s too, and a popular choice for upgrades ever since.

Dimpled and combi rotors / discs

Unlike cross drilled items, dimpled discs have holes that don’t pass all the way through. This type of surface treatment is chiefly to prevent the stress fracturing often associated with the extreme use of cross drilled rotors. It also helps with gas dispersal by giving gases a temporary place to go while under the pad.

Combi discs, often referred to as ‘drilled and grooved’, take the benefits from both grooves and either dimpling or drilling (or sometimes both).

Ceramic rotors / discs performance brakes

Many high-end performance cars come with ceramic (or more accurately; carbon fiber composite-reinforced) brake discs. What you may not know is that the process of producing these initially began in the UK, in an endeavor to make train axles lighter. True story.

Anyway, ceramic discs offer up to a 50-percent weight saving over normal cast-iron performance brakes. They also tend to last significantly longer. The only downside is the cost,. Even aftermarket ceramic discs can come in at around $2000 a pop… and that’s per rotor. Ouch!

Performance brakes: big rotor / disc conversions

Aside from standard-sized discs with various surface treatments, the most common upgrade in pursuit of better performance brakes is fitting thicker, larger diameter discs. Obviously this is a little more involved but the idea is to give greater leverage (to improve stopping power) while helping to prevent fade and warping.

There’s a few different approaches here. Some simply fit the larger discs and calipers from a higher spec’d model. Very often, these will bolt straight on too. Beware though, some of these OEM+ upgrades may require a hub or suspension knuckle swap. It always pays to do your research first.

Others prefer a specialist aftermarket kit with larger multi-piston calipers that’s designed specifically to do the job. While these big brake kits (BBKs) are rarely cheap, they do tend to offer the ultimate in performance. They will also come with everything you need to get them on the car without the need for any fabrication.

The only real limiting factor with running any big brake setup is the size of your wheels. But, although there are plenty of ‘lightweight’ versions with separate alloy bells and calipers, it’s also worth remembering that bigger one-piece discs will often be heavier. There’s no such thing as performance brakes that are ‘too’ good and that’s true, but there is such a thing as overkill. Adding masses of weight, especially when it’s not needed, won’t do anything for overall performance.

Performance brakes: calipers

Floating calipers

A floating caliper system comes in two parts; the caliper body which is designed to move and the slider that stays firmly bolted to the chassis. These commonly have their piston (or multiple pistons) mounted to the back of the rotor. When you hit the stoppers, these first push the inner pad against the disc. It then pulls the caliper body and outer pad back against the other side. It’s a simple, effective design and relatively cheap to produce. It’s also by far the most common on road cars.

Fixed calipers

As the name suggests, fixed calipers don’t move in relation to the disc. Instead, they use one or more pairs of opposing pistons to clamp the pads against it. As standard, these are only fitted to high performance motors (you’ll find them on plenty of 350Zs, Subarus and the like). They’re also what you’ll find in a BBK.

These calipers are often machined from lightweight aluminum. They also come with the added advantage that they’ll often take a bigger pad. The number of pistons and size of these varies between 2-pot calipers right up to rather crazy 16-pot items. The rule of thumb is that more pistons enables a greater, and more even, clamping force. Although admittedly, some of the larger units go well into the realms of overkill. 4-8 pots is more than enough!

Uprated brake pads

Brake pads come in all shapes and sizes, but they will always be specific to your vehicle (or aftermarket performance brakes caliper). What makes uprated pads different to standard is simply the makeup of the friction surface. This is what’s known as the compound.

Different compounds, containing everything from semi-metallic, ceramic and organic materials, give different braking characteristics. They are also susceptible to different operating temperatures and durability. That means finding the right one is dependent on not just the weight of the car, but also how you use it.

Arguably the most important characteristic of any compound is its hardness. A soft compound will suit aggressive track driving but will wear out pretty quickly. On the other hand, a hard compound will be more likely to succumb to fade under extreme use.

As we’ve already said heat is both good and bad for braking, pads need some to work. In some cases, not enough can be just as devastating as too much. Many hardcore race pads don’t bite effectively until they’ve been suitably warmed up. Obviously this doesn’t lend itself too well to normal road driving on a cold winter morning!

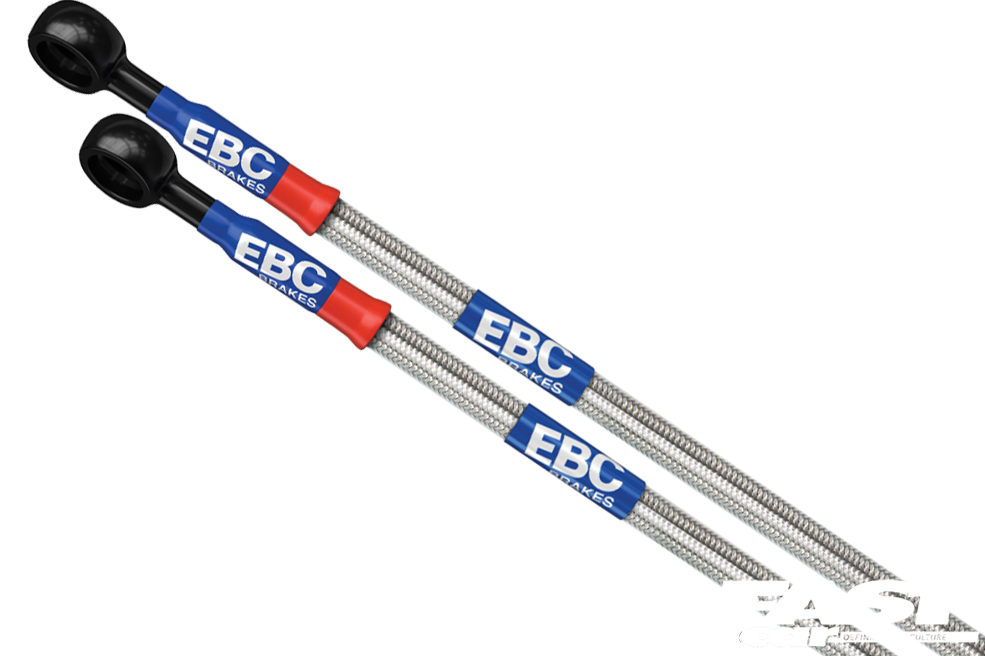

Performance brake hoses

These are the flexible pipes that carry the hydraulic fluid to the calipers from the solid ‘hard lines’ that snake from the master cylinder to all four corners of the car. On most standard vehicles, these hoses are made from durable rubber. However, this comes with one inherent problem; they can often flex or bulge under the immense fluid pressure caused by constant heavy breaking. This is why many track or fast road drivers choose to replace them with a set of aftermarket braided steel lines. Steel hoses can resist much higher pressures. They also give you a less ‘spongy’ feel, and tend to be much more resilient to knocks and scrapes.

Fluid for performance brakes

It’s a common misconception that any old brake fluid will do for your performance brakes. In reality, brake fluid is a hygroscopic liquid which means it absorbs moisture from the atmosphere over time. This moisture eventually lowers its effective boiling point. So, fluid that’s been working its way around the system for a long time obviously isn’t ideal for performance. This is the reason that regular testing and fluid changes are essential to keep stopping power at an optimum.

Brake fluid temperature resistance is rated on the ‘DOT’ scale. The higher the number on the bottle, the higher its effective boiling point. Standard spec fluids all come in at around DOT 3 or 4 nowadays. However, as you’d imagine, many performance formulas on the market designed for more extreme use generally have a higher DOT number. DOT 5 fluids have become a common upgrade in recent years. There are even a few hardcore DOT 6 racing fluids out there now too.

Want to know more? Check out our brake fluid guide.

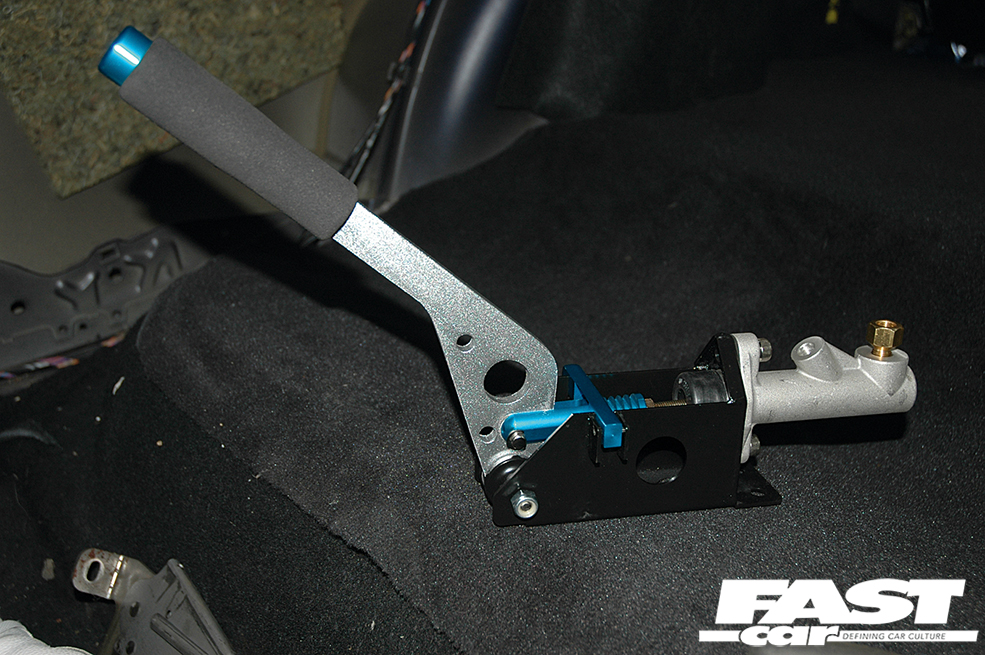

Handbrakes

The handbrake is a system that activates the rear brakes via a lever or button. It has two uses; a parking brake and an emergency brake, just in case the hydraulic system fails. The second function is the reason that you need a separate item for a UK MoT. Rear BBKs often need a separate non-hydraulic ‘spot caliper’ just to keep everything road legal.

There are a couple of handbrake upgrades starting with the ‘drift knob’. This replaces the standard sprung handbrake button with a knob that you have to physically pull out to lock. Unlike with the standard item, the handbrake won’t stay on when you let go.

Alternatively, there are also hydraulic handbrake systems. These simply plumb into the rear brake lines meaning you can lock up the rear wheels at just about any speed. The downside is you’ll still need an extra cable/electrically-operated item if you need to pass an MoT.