Hunt vs Lauda was a motorsport rivalry so strong that it broke into mainstream Hollywood. This is the story of two of F1’s greats.

It’s an age-old cliché. What happens when you pitch an extravagant extrovert against a calculated introvert? In fact, you could argue that the same (or at least, a similar) recipe is what led to the great battle between Prost vs Senna as well. In this case, it was James Hunt that took up the role of extrovert; a man known arguably more for his partying antics than even his extreme speed in a race car. Meanwhile, on the other side of the ring, Niki Lauda preferred to let his driving do the talking. The pair would go head to head in a battle full of twists and turns, so buckle up, this story is one that earned its place in the history books.

The first steps in F1

To get into F1, you need talent. But you also need money. A lot of it. How you get that money varies from driver to driver. These days, if you’re lucky enough, you might get an F1 seat if you’re part of a driver academy for one of the big teams. Or, you might be able to get behind the wheel if you bring enough sponsorship money with you. Back in Hunt and Lauda’s day though, things were a little different. Lauda, a man from a wealthy background, managed to convince a bank to lend him enough money to bag a seat with a March chassis, while Hunt got on the grid after befriending affluent aspiring team owner, Lord Hesketh – ironically, also running a March chassis.

This occurred at slightly different times at the start of the 1970s, and it wasn’t until 1973 that the pair would both be on the F1 grid together; by then, Lauda, had moved across to BRM which was a former top team nearing its demise. That year, Jackie Stewart won his third and final championship, but lower down the order, Hunt impressed. Despite only undertaking a part-season, the Englishman nabbed two podium finishes and never finished outside the top 10. For that, he earned an impressive eighth place in the final series standings. Lauda, meanwhile, struggled with an uncompetitive car, his best result being fifth place at the Belgian Grand Prix amidst a sea of disappointment.

1974 – differing fortunes

The following year, it was all change. Lauda landed a dream move to Ferrari through the potential he had shown glimpses of in the previous year’s BRM, and as Hunt struggled with an increasingly unreliable Hesketh-run March, the Austrian finished 1974 as the higher-placed of the two. Though, at this point, there still wasn’t much of a rivalry – if any – between the pair to speak of. In fact, it’s doubtful that Hunt would even have been on Lauda’s radar at this point. Sure, the Brit was quick, but he was feeling the effects of competing for a privateer team.

Lauda, meanwhile, had managed to wrangle enough performance out of his Ferrari to be leading the championship mid-way through the season. Though, five straight retirements at the back end of the year would ultimately drop him down to fourth in the standings, behind team-mate Clay Regazzoni who had been the first of the two to jump ship from BRM to Ferrari. Despite Regazzoni’s best efforts, neither Ferrari ace would win the title. Instead, that honor went to McLaren’s Emerson Fittipaldi.

1975 – Lauda returns Ferrari to the limelight

Having come so close the year prior, Lauda made amends in 1975 and had a year to remember. He picked up five grand prix victories en route to his first World Drivers’ Championship, and with Regazzoni also on form, Ferrari claimed its first constructor’s championship title since 1964!

On Hunt’s side of the paddock, Hesketh had finally ditched their aging March and built their own car. It was reasonably quick, too. Quick enough to take victory at Zandvoort. But let’s be real, Hesketh isn’t Ferrari or McLaren. So although Hunt did well to finish fourth in the overall standings, it was never going to be a title-contending season. To rub salt into the wound, Lord Hesketh’s bank balance had finally taken enough of a hit to worry him. And so, that was that. The team was closing up shop, and James Hunt was out of a drive. That is, until news emerged from McLaren.

Emerson Fittipaldi had handed in his notice, and the double World Drivers’ Champion would be off to compete for his family team (a move that would prove to be more of a backwards step than he might have anticipated). That meant that suddenly there was an opening at one of the best teams on the F1 grid. And I’m sure you can imagine who wanted to fill it…

1976

So, here we are, the year depicted as the main focus of the film, Rush. The scene had been set perfectly. Reigning champion Lauda would defend his title with Ferrari, while the Italians’ greatest rivals McLaren would field the fiery and eager Hunt. Until now, the pair of them had never truly gone head to head, only sparring in passing glances. But boy did it kick off once they had equal machinery.

Wasting no time, Hunt promptly put his McLaren on pole for the season-opening Brazilian Grand Prix, with Lauda alongside him on the front row. Lauda would win the race though, with Hunt’s car succumbing to a terrifying ‘sticky throttle’. Lauda won the second round too, this time in South Africa, with Hunt tailing him home. The third race at Long Beach once again resulted in Hunt sitting on the sidelines after coming together with Patrick Depailler, while Lauda further added to his points tally with a second-place finish. By the time the Spanish Grand Prix rolled around, Hunt already had some notable ground to make up.

But, fortune seemed to favor the Brit. Between races, Lauda had managed to break his ribs in a tractor accident of all things, meaning that although he was still allowed to race, he wasn’t exactly at full fitness. The result? Hunt wins, Lauda finishes second. At least, that’s how it finished at the flag. During a post-event inspection, the FIA governing body decided that Hunt’s car was a mere 1.8cm too wide. To you or I, that might sound like a negligible offence, but to the FIA, that was worthy of getting Hunt kicked out of the race. Maybe fortune wasn’t on his side after all. Mechanical problems in Belgium and Monaco compounded his woes, with Lauda again making strides at the front.

No stopping Lauda?

At this point, the Austrian’s advantage in the championship was huge. He had collected a total of 51 points by this stage, with his closest challenger being teammate Regazzoni with a comparatively poultry 15. Bear in mind, this was at a time when points were much harder to come by in F1, as they only extended down to the sixth finisher. As Lauda was proving, if you could string together a chain of wins and podiums back then, you were practically untouchable.

In Sweden, a brief interlude in Ferrari and McLaren’s successes saw the freakish six-wheeled Tyrrells dominate the weekend, but it was back to business as usual in France for Round 7. There, Hunt grabbed a much-needed swing of points. The Brit converted pole to victory, while Lauda retired with crankshaft dramas. With the British Grand Prix just around the corner, it appeared as though the home favorite had finally found some luck.

The British Grand Prix

After qualifying at Brands Hatch, it did indeed look as though Hunt was in with a shout. Sure, Lauda had taken another pole, but Hunt was right there alongside him on the front row. Of everyone on the grid though, it was Lauda’s teammate Regazzoni who got the best start, jumping both the Lotus of Mario Andretti and Hunt’s McLaren. In fact, with a tempting gap in front of him, Regazzoni even dared to launch past Lauda, but turn one at Brands is a tricky affair, and such a move resulted in the pair coming to blows. It was the sort of gung-ho corner entry that the likes of Senna and Prost would go on to replicate many years later at Suzuka, although this time the outcome was far less dire for Ferrari’s championship hopes.

Regazzoni span out, but Lauda wrestled his car into line and resumed the lead of the race. Unfortunately for Hunt, the Brit would get tangled in the ensuing melee, wrecking the McLaren’s rear suspension. Here we go again…

It wasn’t uncommon in the ’70s for the drivers of damaged cars to swap into the team’s spare one if an opening lap crash caused the race to be halted, and, given that a clean-up operation was underway at Paddock Hill Bend, that’s exactly what Hunt attempted to do. The FIA were having none of it though. In their minds, such a move would be illegal, as by the time the race had been halted the cars had already technically completed the first lap. Arguments ensue.

However, while all the fuss was being kicked up, the plucky engineers in the McLaren garage managed to get Hunt’s broken suspension fixed. So, no need for the spare car. Until, yet again, the FIA decided that wasn’t adequate. As the fixed car hadn’t completed the first lap like the others on the grid had, it wouldn’t be allowed to take the restart either. Disaster.

In 99% of cases that would be that. But, no, there was another twist in the tale. See, while all of this had been happening, the 100,000 fans around the circuit had become pretty aggravated about the whole scenario. In the eyes of the paying public, they were witnessing an injustice, and boy did they let the FIA know. Remarkably, the officials did eventually back down. And so, Hunt was allowed to take the restart after all. I’m not exactly sure what the moral of the story here is…

As if written in the stars, a close battle on track ignited, culminating in Hunt passing Lauda at the hairpin, and sending the crowd into raptures as a result. From there, gearbox issues would see Lauda helpless to retaliate, and having been helped along by the home crowd, Hunt was able to mop up the points for victory. As a sweetener, it soon emerged that after a successful appeal, Hunt’s win in Spain had been reinstated. Game on. But wait, hold on, if you thought we were all out of curveballs, prepare to be amazed. With the fans having left the track gleefully, the FIA promptly disqualified Hunt for an illegal restart. The win was Lauda’s.

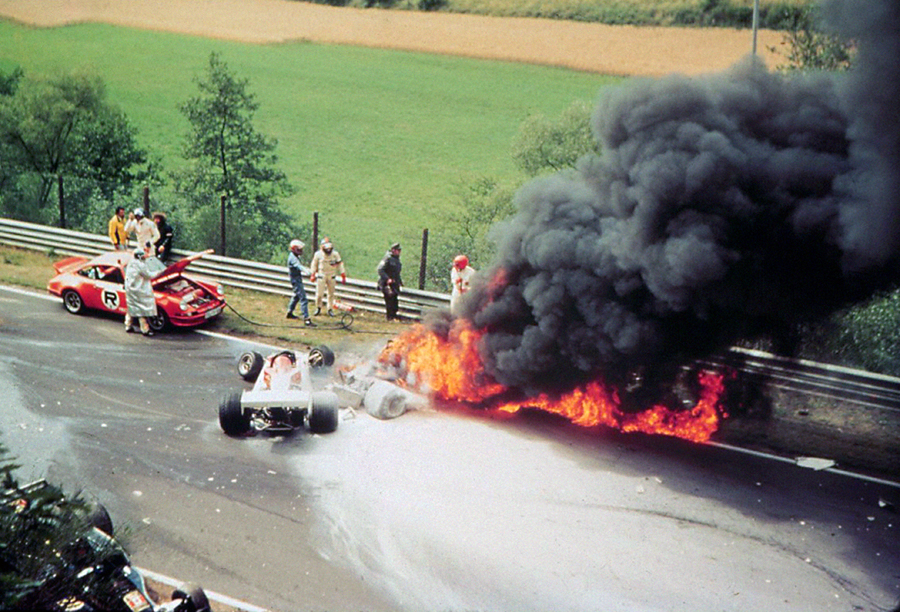

Tragedy at The Green Hell

Next up, the Nürburgring, and whereas it had been uncharacteristically sunny in the UK, the German Grand Prix weekend offered a rather more mixed climate to deal with. The Nordschleife was dangerous enough for F1 cars to begin with, but add uncertain conditions into the equation, and you’re asking for trouble. Lauda knew this, and earlier in the year he had unsuccessfully tried to get the track boycotted in favor of the safer Hockenheimring. That decisive vote would prove to be a fateful one.

With reports of rain on certain parts of the track, both Hunt and Lauda started the race on wet tires. However, it soon became clear that that was the wrong call, as drivers with slick-shod cars began to surge past them. Inevitably, the call was made to swap over to slick tires, by which point neither Hunt nor Lauda were in great positions, but Lauda in particular had ground to make up to regain contact with Hunt. So, as any racing driver would, he pushed hard. Too hard.

In the depths of the Green Hell’s forests, Lauda suffered a high-speed impact with a wall. The Ferrari burst into flames and rebounded onto the circuit, where it was collected by the car of Harald Ertl. Ertl, Brett Lunger, Arturio Merzario, and Guy Edwards all abandoned their own cars on the spot to rush over and come to Lauda’s aid. Merzario in particular showed admirable bravery, reaching into the flames to undo Lauda’s seatbelts. Their efforts, and of course the efforts of the medical staff who received Lauda at hospital, undoubtedly are what saved him from certain death.

Nonetheless, the extent of his injuries were life changing. His lungs had to be vacuumed to get rid of toxic material and he suffered widespread burns, particularly across his right ear and scalp. He also suffered damage to his tear ducts, which caused complications with his vision. That alone would be bad enough, but Lauda’s time in hospital was made even worse by some of the people he encountered.

A brazen photographer snuck into Lauda’s room disguised as a doctor and took pictures of him laying in bed, unable to say or do anything in response. Fortunately, the slimy rascal was caught and forbidden from publishing the images. There was also an incident with a priest. Lauda says that the priest in question merely turned up, gave him his last rites, and left again, without any sort of compassion or encouragement. Mind you, you could argue this was a blessing in disguise, as Lauda was so upset by the priest’s behavior, he vowed not to die in that hospital bed. Incredibly, despite all of this, he was back in a Ferrari F1 car just six weeks later.

Lauda’s remarkable return

During that time though, the F1 show went on. Ferrari didn’t attend the eleventh race of the year in Lauda’s home event at the Austrian Grand Prix, but Hunt of course did. The trouble for Hunt was that, so did everybody else, and consequently he only managed fourth place while John Watson took the victory for Penske. Next time out at Zandvoort, Hunt did manage to win the race, despite Regazzoni and Watson’s best efforts. With Lauda obviously not scoring, Hunt was now within striking distance.

The thirteenth race of the year was to be held at Monza – the home of the Italian Grand Prix and the Ferrari-loving Tifosi. And, poetically, it was here where Lauda would return to the cockpit of one of the famous red cars. Incredibly, he outpaced both Regazzoni and new Ferrari wildcard Carlos Reutemann in qualifying. To make things even better for Lauda, Hunt started the race right at the back following a fuel infringement. Perhaps in an eagerness to regain ground, Hunt ended up in the gravel trap and out of the race, while Lauda steered the Ferrari home to fourth place.

However, as the championship moved across to North America for the next two rounds, Hunt would find form just when he needed it. Two victories compared to an eighth- and third-placed finish for Lauda meant that there would indeed be a final-round showdown in Japan to end the year.

The Japanese Grand Prix

Going into the final race at Fuji Speedway, the situation was this: Lauda had 68 points to his name, and Hunt had 65. Nine points remained on the table, meaning that as long as Lauda could simply follow Hunt home to the flag, he’d be a valiant double World Champion.

Qualifying went well for the Austrian. Although Hunt was on the front row, Lauda would start just behind in third. But, as if the stakes weren’t already high enough, the heavens opened, and the track was deluged. It’s not uncommon to get this sort of severe wet weather in Japan. Rain-instigated red flags are no rare thing in the Japanese Super GT and Super Formula championships of today, but back then, F1 had a show to put on, so the decision was made to go ahead with the race despite the downpour.

As you can imagine, visibility was atrocious. The spray kicked up from the cars meant that if you were even two or three positions behind the leader, you might as well be driving the track by memory rather than by eyesight. That wasn’t a particular issue for Hunt though, who had vaulted into the lead of the race in the early stages. Lauda, meanwhile, wasn’t having such a fun time. Having dropped to fifth, and now all too aware of the danger that can strike in adverse racing environments, he decided that enough was enough. On lap three, Lauda pulled into the pit lane and simply stepped out of the car. Although probably shocked by the novelty of the situation, the Ferrari crew couldn’t exactly argue with Lauda’s choice. He would go home knowing that Hunt was the champion this year, but at least he’d be going home.

It’s also worth noting that Lauda wasn’t the only competitor to withdraw. Fittipaldi, Carlos Pace, and Larry Perkins joined him in pit row. Hunt, however, probably would’ve stayed out on track even if a tsunami hit.

From there, it looked as though the title was neatly wrapped up for Hunt, but this being Japan, the weather wasn’t done yet. As the race wore on, the track began to dry. In fact, it dried out so much that a distinct dry racing line had emerged. This wasn’t ideal for Hunt’s wet-weather tires, which degraded rapidly as the Brit made little effort to preserve them. As a result, both Depailler and Andretti caught and passed him. Third would still have been enough to capitalize on Lauda’s retirement though. But then, Hunt’s tires gave up for good. Having dragged the McLaren to his pit box, Hunt received a fresh set of rubber, emerging back onto the track in fifth. If he wanted that title, he had work to do.

Fortunately for hunt, there was yet another twist in the tail. Remember Reutemann, the Ferrari wildcard at Monza? Well, Regazzoni caught wind of the fact that Reutemann was set to take his seat at Ferrari in 1977, and knowing that, the Swiss felt little loyalty towards the Prancing Horse anymore. So, when Hunt appeared behind him, Regazzoni didn’t put up the strongest of fights. Though, in fairness, Hunt’s fresh tire advantage should have been enough to see him through anyway. Following in the wheel tracks of Depailler, Hunt made his way past Alan Jones too, and eventually crossed the line in third. After this absolute rollercoaster of a year, Hunt had done it. He was champion by one single point.

What did the future hold?

In the winter months and beyond, Hunt became a national darling in the UK, and would even go on to commentate on F1 alongside Murray Walker once his driving career ended just three years after winning the 1976 championship. As for Lauda, well if you feel that he should’ve been the rightful winner of the ’76 championship, don’t worry – he bounced back the following year and claimed the 1977 title with two races to spare! And, after a brief hiatus, he’d even go on to claim a third title in 1984 while driving for Hunt’s old team – McLaren.

In fact, Lauda would go on to remain a beloved member of the F1 paddock for decades to come, assisting with the running of multiple race teams, most notably Mercedes up until his passing in 2019, aged 70. Sadly, Hunt didn’t get to enjoy such longevity. Despite everything that Lauda had been through, it’s almost little surprise that he outlived his great ’76 rival. Hunt’s hedonistic ways would eventually catch up to him in 1993, when he died of a heart attack at just 45 years of age. In a way, the fates of these two drivers summarizes their respective personalities and careers to a tee. Hunt shone brightly across just six and a half F1 seasons (relatively few for a driver of his caliber), whereas Lauda’s career always contained an element of long-term thinking.

This battle of wills would’ve made for a great spectacle on its own, but when you throw in all the adversity that struck in 1976, the story becomes one that will live on in F1 folklore forever. Someone should make a movie of it, don’t you think?